Martin Ries dissects The Persistence of Memory

Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) showed precocious gifts in the local Catholic schools in Figueras Spain where he was born, as well as at the National School of Fine Arts in Madrid where he studied art. He exhibited decided megalomania, and impressed everyone as a troublemaker. He was expelled from school more than once and served jail terms for anti-government activities. While a student he met poet Federico Garcia Lorca, who was later murdered during the Civil War. He wrote the script for the film, Un Chien andalou with Spanish-born film maker Luis Buňuel before joining or even meeting the Surrealists.

Despite bizarre activities and outlandish statements, the sum total of Dalí’s work, including his writings, represents much more than eccentricity, narcissism and slick posturing. Thus the tendency to dismiss Dalí is not completely fair, considering his early articles in Catalonian and Spanish vanguard magazines during the 1920s, that are serious and without his familiar later pretension.

In 1927, Dalí discovered Surrealism in the art magazines. It was a revelation, and he painted Blood Is Sweeter than Honey, which featured images that continued to obsess him.

In the 1920s-30s, the Austrian psychologist Sigmund Freud’s theories on the unconscious mind became so pervasive as to be taken for granted by the Surrealists. Freud used the psychoanalytic device of free association to trace the symbolic meaning of dream imagery to its source in the unconscious; Dalí applied the same method to his pictorial imagery.

Based on psychoanalytic studies of paranoiac dementia, Dalí consciously charged his paintings with psychological meaning which he called his “paranoiac-critical method”, using countless symbols of persecution mania, sharp instruments (castration), sexual fetishes, and phallic images, many taken directly from case histories of paranoia in Dr. Richard von Krafft-Ebing's Psychopathia Sexualis, as well as from Freud’s works.

Paranoia is a mental disease characterized by delusions and projections of personal conflicts ascribed to the supposed hostility of others. Dalí’s work imitates paranoiac conditions, because while the paranoiac is able to find proof of persecution, Dali only simulated the illness. He used paranoia less in the psychiatric sense than the etymological sense: para, meaning alternate, noia meaning mind. Thus, his "paranoiac-critical method" became a forced inspiration as Dalí submitted his paintings at once to the caprice of dream and wide-awake calculation. His images, based on readings in psychiatry, eventually began displacing experiences drawn from his own psyche.

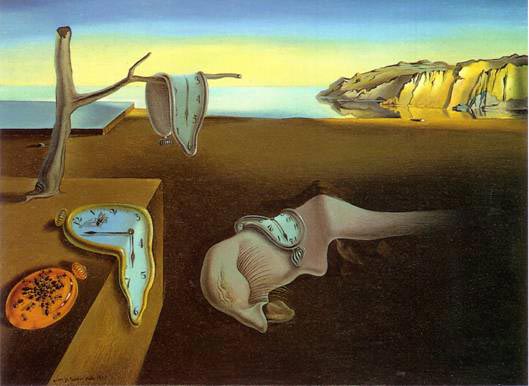

In The Persistence of Memory (1931, oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art), the long-venerated Newtonian cosmos, shattered by Einstein’s special theory of relativity in the early part of the 20th century, had to be discarded and replaced. “At rest” was no longer a reality as the philosophical perception of time shifted from absolute to an eternal becoming. There was much discussion on questions of when time began, will it exist forever, and had it always existed. French philosopher Henri Bergson is supposed to have quipped: “Time is nature’s way of preventing everything from happening at once.” The Church thought of time as eternity, citing medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas’ Summa theologiae where he compares completeness, perfection, and infinity, to God.

The deep perspective in Persistence suggests time past, with the viewer deserted and lost in infinity. Interestingly, Salvador (“Saviour”) Dalí’s anti-clerical sentiment is reflected in his use of Christian and Freudian images in the painting; and as if to emphasize the reality of his hallucinations, his surreal iconography is placed in the landscape of the bay at Port Lligat on the Costa Brava, his home and studio. Although he describes the origin of the soft watches as derived from dreaming of Camembert cheese, Marcel Jean, in his History of Surrealist Painting, says they symbolize impotence: montre not only means “watch” in French, but is also the imperative form of the verb montrer, “to show”. A sick child must show his tongue to the doctor, montrer la molle, which sounds the same as la montre molle “soft watch”. Usually we think of these bent watches as referring to Einstein's theory in which our world is becoming a spatio-temporal continuum; the world's concept of time and space was certainly changing. The three open and vulnerable watches (past, present, future?) are within orthogonals that point to the top center of the painting (heaven?).

According to Freud, menstrual periodicity transforms the concept of time into a feminine symbol, and the fourth watch, closed, hard and impregnable, has been diagnosed as a feminine symbol. Certainly this watch in the foreground is a vital red, while the middle-ground watch is softened to orange, and the background timepiece is a lifeless gray. Could the hands on the flaccid watches refer to the traditional medical-scientific sign for male?

There are further symbolisms in the painting. Ants usually suggest putrefaction and decay; the rigid watch is attacked by scavenger ants, indicating the inorganic is becoming organic and vulnerable. However, as the watch is closed and red with life, time is unattainable and the ants attack without success, implying triumph over death and decay via procreation or immortality. In Christian doctrine, ants signify provident man, the one who chooses the true doctrine and rejects heresy. The fly, on the other hand, has long been considered a bearer of pestilence and evil (Lord of the Flies, or Beelzebub, is from Ba al-z' bub, lord + fly, a god of the ancient Philistines, averter of insects). In Christian symbology, the fly symbolizes evil.

The amoeba or fetal image suggests the primordial beginnings of life, and like a lost soul in infinity, is stranded on a barren beach with its life-giving water (holy water?) in the far distance. This fetal image, usually interpreted as a self-portrait, appears in several other paintings, including The Great Masturbator. The soft tongue, similar to the limp watches, is a well known Freudian symbol for the penis; Dali, in his Secret Life of Salvador Dali, overtly makes public his anxieties about sexual dysfunction. Trees, tall and erect, are male symbols according to Freud, but this tree is scrawny and lifeless. The extending phallic branch, with its post-coital watch, points to rock formations which in actuality are the granite outcroppings above the Bay of Cullero near Dali's home. “Geology has an oppressive melancholy,” stated the artist, “this melancholy has its course in the idea that time is working against it.” Again, the rock is a symbol of Christian steadfastness, and suggests the antithesis of the biological objects which are subject to the laws of change and disintegration.

According to medieval Christian legend, the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil withered when Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit. Thus the dead tree in the Italian Gothic painter and architect Giotto’s Lamentation, and later, in the works of Italian Renaissance artists Resurrection by della Francesca and Fall and Expulsion by Michelangelo, all refer to original sin, otherwise known as Freud’s Oedipus Complex. The cubes on the left may possibly have some reference to Cubism, although again, they are symbols of stability in Christian iconology.

Ants, the fly, yielding watches, foetus, open horizon, all suggest transitory, non-persisting time.

Realism dominates Dalí's work because the visual logic of the picture makes itself felt in the sense that the dreamlike emphasis can be conveyed only when the objects are neither stylized nor abstract, but factually rendered. Only in this way can the iconology be realized and the “irrationalism” of Dalí express itself. It is interesting that the irrationalism and hyperbole of Surrealism, and especially of Dalí, are not very highly regarded in the art world today (this paper originally written in 1991), while abstraction continues to grow and hold our attention. Even Freudian dream theory is now challenged; many neuroscientists and psychiatrists argue that dreams do not stem from unacceptable hidden desires and fears but actually are caused by spontaneous electrochemical signals in the brain which we cannot help investing with meaning.

But Dalí continues to fascinate.

An earlier version of this paper was commissioned and published by St. James Press, for Contemporary Masterworks, Colin Naylor, ed., London & Chicago, 1991. Professor Emeritus at Long Island University, Martin Ries, artist and art historian, was Assistant Director of the Hudson River Museum, and studied art history at Hunter College. He has published widely, and exhibited his works in the United States and elsewhere. For more see http://www.martinries.com/

Article first published 08/10/08

Comments are now closed for this article