How Integrated Natural Resource Management improves water security for small farmers

Dinabandhu Karmakar, Professional Assistance for Development Action (PRADAN), India

Why does PRADAN support small decentralized farm-based rainwater harvesting rather than big projects? In short, we made a commitment to poor, small-holder farmers to ensure happy, self-sustainable livelihoods in their own farms. Fifty seven percent of Indian rural households own some land, the majority of farms less than one hectare and about half depend entirely on seasonal rain [1]. Many of these farmers do not have access to irrigation projects tied to big dams and government–sponsored canals programmes.

We work in central India, an area of undulating terrains with large numbers of tribal peoples who until 3-4 generations ago were forest dwellers and hence not experienced as farmers.

India is host to a large number of poor and hungry people, ahead of countries in Africa; but the conditions of smallholders are very similar and we are now trying to spread our experience to some of the African countries.

The development of big dams and reservoirs does not stop the depletion of upstream catchment areas; instead, water is stored behind dams for irrigating downstream lands. That means the land and people upstream have no water reserves. Another problem is that good water sources are historically owned by better-off families. Farms that receive the water downstream are those that belong to the better off, with the poor people being left out. As they have no resources or savings, the poor are unable to create their own infrastructure to irrigate their crops. As they cannot harvest water, the biggest problem is the uneven distribution of rainfall throughout the year [2]. Rain comes in 3-4 months from June-September [3], while water is need all year round. There are no government programmes to ensure water supply to small holders. This is one of the most important challenges in these pockets of poverty in India and probably also across the world.

Here are some data from Colombia University [4]: India has 200 m3 of water storage per capita while the US and China has 1 960 and 1 100 m3 respectively. The world average is 900 m3. I estimated that a small-holder farmer needs 500 m3 per capita to meet basic needs and to have a good livelihood; enough to farm food and have drinking water and water for household use.

Though the Indian government has talked about a national policy of water and equality and justice in sharing water, there is until now no effort to quantify the minimum amount of water required to ensure successful livelihoods. In most cases, there are policy makers claiming that small-holder farmers are of little use, that they are uneconomical, and unable to sustain themselves. So big farms come in to consolidate the land and start growing crops instead. But with a population of over 1.2 billion, it is not possible that so many thousands of people in India will be able to go to the city and get service and public sector jobs. That is why farming has to be there, small holders must be supported and their water requirement has to be met. And farm- based water harvesting is most appropriate in the undulated terrains of central and eastern Indian plateau.

If you look at the map of the regions, the Himalayas are the undulating hilly terrain across the north, similar to the condition in the central Indian plateau. This leaves water flowing to the Ganges plains and coastal India in between. With the creation of dams, canals and all, the poorer people living in the hills and undulating areas are left with nothing. This is a typical dynamic between upstream and downstream areas at the local level as well as the national level. Upstream, the run-off water and production of crops is uncertain, the local economy is weak, people migrate to get jobs and earn wages; they are politically weak [5] and no-one works with them to ensure that they have access to their rights. Incidentally, this area is also rich with metal ores. There is hematite, bauxite and other minerals, and companies are eager to explore the area for mining. This is the problem in upstream areas, which also goes to benefit people in downstream area. They have water for their crops, they get cheap migrant labour from upstream areas to work in their farms, they are politically strong and can influence government policies; they have strong farmer’s lobby groups and ministerial support, and use almost-pure canal water while paying minimal tax.

Poverty and insecurity of water supply go together in the upstream areas. Once the water supply goes down, people are dragged down with it. This is a very challenging problem to address. Society has decided to leave some people poor, against the precept of ‘live and let-live’. The blind pursuit of GDP and growth is taking away everything, even the spirit of letting people live. Open-state power is also behind this, politicians and leaders ignore the fact that they are supposed to serve poor people. Deprivation of local people is still happening, even with independence and democracy. Investment is controlled by outsiders, they come to exploit and don’t think of a long-term policy to invest for the benefit of the local people and the region.

In 2005, we took up a project with Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research and went to the villages to see what was happening. There was a drought in the area and the crops were failing. A woman was harvesting a failed crop. We asked her why she was doing that when there is no crop, to which she replied “my husband told me to do it”. What happens when a drought comes and the crop fails is that the able-bodied men leave the village to go to the urban centres to get waged labour. The women, the children and the elderly are left behind to somehow manage. These are the lands that when it rains in June, July, and August, the crops grow. But later, if there is no rain, the crops will fail. So, all the rain that falls in the rainy season runs off into rivers and the reservoirs behind big dams that supply water to irrigate the land downstream, while people living upstream cannot save their crop.

The investment needed to irrigate a hectare of land is 300 000 rupees and sometimes more. But the government only allocates 12 o0o rupees to rain-fed areas, less than 1/10 of what is required. So with such a policy, one cannot reduce poverty. Our experience shows that if similar financial resource allocations are made for so called rain-fed areas as irrigated areas, then at least 80 % of poor people in areas where rainfall is 600 mm or more could be assured of the necessary irrigation water.

Technology also matters. The government’s choice of technology seems to be solely based on benefiting the downstream areas and residents; even though harmless and minimal interventions can assure water security for the poor. This is where our Integrated Natural Resource Management approach comes in to make sure that every family gets its water. If 1 000 mm of rain falls, every square metre gets 1 cubic metre of rainwater, that rainwater can be harvested and stored so three to four crops [6] could be grown from the same piece of land. This is the potential of small scale decentralized farm-based rain harvesting. Figure 1 depicts what happens when farmers are helped to harvest rainwater in their own fields.

Figure 1 On-farm rain-harvesting improves productivity and income

We designate 5 % of people’s plot of land to be used for a water harvesting tank. The excavated soil is used to strengthen the field bunds (embankments at the boundaries of the plots) and/or create raised beds for planting early vegetables while the water is saved also for rice production. Farmers also rear fish in those tanks to provide a source of protein to families.

This has already been demonstrated in the central Indian plateau and eastern plateau to enhance water security and improve living conditions. Thousands of farmers are now adopting this system. Our Indian government has given a job assurance programme to anyone who wants to do some manual work to get 100 days’ work in a year. This is a good policy to give wages to the wage earner. To take advantage of the programme, we are trying to convert that into asset building with our model, so if farmers get 100 days of work, he or she can actually work in their own field to create a small water reservoir. This has allowed the idea to spread. The governments in 5-6 states have responded positively to this programme and are spreading this water harvesting approach with their own people.

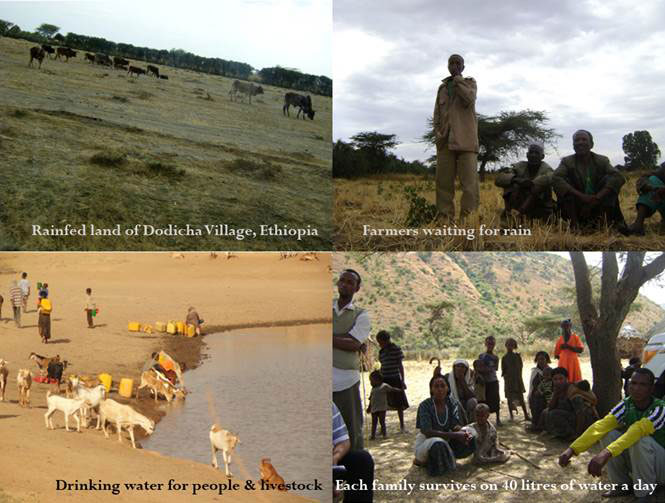

We have also had a positive response from some African countries, particularly Ethiopia, whose agencies have visited India and said that this is a very positive experience and we have started working there also. I visited the Rift Valley in December 2012 (see Figure 2), where people are trying to change things.

Figure 2 Access to water a severe problem in Ethiopia

They have problems accessing drinking water, with most water being muddy and unsafe. A woman I met travels 4 km there and back to get water from a stream. All local animals, cattle, goats, donkeys, etc swim in and drink from same stream. We have started similar water harvesting approach in Ethiopia where much of the country is also hilly and prone to erosion with no provision for harvesting runoff water. Access to water is not just a problem for the Rift Valley; it is much more widespread in Ethiopia [7] and also in sub-Saharan Africa [8].

Back in India, we are pro-actively building partnerships with NGOs to influence local governments and seeking support from our stakeholders and sponsors to spread our approach beyond current operating areas, to countries around the world to benefit the smallholders.

Dinabandhu was speaker on World Water Day 22 March 2013 as part of the Colours of Water art/science/music festival 12-28 March 2013 (see https://www.i-sis.org.uk/coloursofwater/). Pradan featured another water harvesting technique in the video installation for the festival, Earth Water & Life (www.pradan.net).

Article first published 10/06/13

Comments are now closed for this article

There are 1 comments on this article.

Rory Short Comment left 17th June 2013 17:05:43

This is an excellent approach because it keeps its eyes on the individual. The problem with the mindset that is so prevalent currently is that it only sees the solution to problems in terms of industrial scale mass production, i.e. large dams and mega irrigation schemes. In the process the individual person and their very real needs and contributions to any solution are completely forgotten.